URLSession “and related classes provide an API for downloading data from … endpoints indicated by URLs.” Most iOS developers are familiar with using the URLSession singleton, shared, which has “reasonable default behavior”, including retrieving data from the actual endpoint represented by the URL specified.

But using shared in all circumstances has some drawbacks.

- In a production app, during development of a new feature, the endpoint may not exist until late in the development cycle. Using

sharedmeans that development of the client-side UI of a new feature is blocked until development of the endpoint is complete. - Because using

sharednecessarily involves network access, use ofsharedin unit tests can cause those unit tests to be slow or to fail altogether. - The endpoint may not return the data needed to exercise all functionality of the app. For example, the app may have a special no-data-was-retrieved state, but if the actual endpoint has data, this state can’t be triggered.

This post presents a solution to these three problems: using a stubbed version of URLSession and using alternate URL variants, both via dependency injection.

Paul Hudson described the URLSession-stubbing technique in this excellent article. My post contains two refinements to his article, both described in the section Acknowledgement.

Getting Started

For the rest of this post, I’ll use a cat-breed endpoint I set up for my earlier post about coding challenges. The endpoint returns JSON with this format:

{

"breeds": [

{

"name": "Abyssinian",

"popularity": 42,

"known_for": "Egyptian appearance",

"photo_url": "https://raceconditionsoftware.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/CatFancy/img/Abyssinian.jpg",

"info_url": "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abyssinian_cat",

"credit": "Josh Adams",

"license": "public_domain",

"description": "The Abyssinian is a breed of domestic short-haired cat ..."

},

{

"name": "Balinese",

"popularity": 51,

"known_for": "plumed tail",

"photo_url": "https://raceconditionsoftware.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/CatFancy/img/Balinese.jpg",

"info_url": "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balinese_cat",

"credit": "Pxhere",

"license": "cc1",

"description": "The Balinese is a long-haired breed of domestic cat ..."

},

...

]

}

How to represent this data in an app’s models is outside the scope of this post, but here is a simplified version of the models I used in my earlier post:

struct Breed: Decodable {

let name: String

let knownFor: String

let popularity: Int

let photoUrl: URL

let infoUrl: URL

let credit: String

let license: String

let description: String

}

struct Breeds: Decodable {

let breeds: [Breed]

}

The code above and indeed all code in this post are in this repo.

For reference, here is how the app described in my earlier post displays this data.

Vanilla URLSession.shared and URL

URLSession is like a protocol in that it represents a contract for retrieving Datas from endpoints. Unlike a protocol, URLSession has an initializer. This initializer takes a URLSessionConfiguration, which is used “to configure the timeout values, caching policies, connection requirements, and other types of information that you intend to use with your URLSession object”. In order to obviate the need to create a URLSessionConfiguration for simple download tasks, Apple provides a URLSession.shared singleton “that gives you a reasonable default behavior for creating tasks”, allowing you “to fetch the contents of a URL to memory with just a few lines of code”.

Here is how URLSession.shared can be used to fetch cat-breed data and convert it to the models shown above. This function and others like it live in an enum called BreedRequester.

static func requestBreedsClassicWithoutInjection(completion: @escaping ([Breed]?) -> ()) {

URLSession.shared.dataTask(with: URL(string: "https://raceconditionsoftware.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/CatFancy/breeds.json")!) { data, _, error in

if

let data = data,

error == nil

{

do {

let decoder = JSONDecoder()

decoder.keyDecodingStrategy = .convertFromSnakeCase

let breeds = try decoder.decode(Breeds.self, from: data)

completion(breeds.breeds)

} catch {

completion(nil)

}

} else {

completion(nil)

}

}.resume()

}

Here is an invocation of that function that uses URLSession.shared:

BreedRequester.requestBreedsClassicWithoutInjection { breeds in

if let breeds {

print("Breed count using classic URLSession.dataTask without injection: \(breeds.count)")

} else {

fatalError("Classic breed-fetching without injection failed.")

}

}

This implementation has the three problems described in the introduction to this post: that the endpoint may not exist during development, that network access in unit tests is slow and flaky, and that a successful response from the endpoint does not permit exercise of the no-data or error cases.

Apple has enhanced URLSession with an async/await implementation. The details of async/await are beyond the scope of this post, but I’ll mention two value propositions of async/await: that the fetch appears, from the caller’s perspective, synchronous, and there is no callback to futz with.

Here is how URLSession.shared, with async/await support, can be used to synchronously fetch cat-breed info and convert it to the models shown above:

static func requestBreedsSyncWithoutInjection() async -> [Breed]? {

do {

let (data, _) = try await URLSession.shared.data(from: URL(string: "https://raceconditionsoftware.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/CatFancy/breeds.json")!)

let decoder = JSONDecoder()

decoder.keyDecodingStrategy = .convertFromSnakeCase

let breeds = try decoder.decode(Breeds.self, from: data)

return breeds.breeds

} catch {

return nil

}

}

Here is an invocation of that function that uses URLSession.shared:

Task {

if let breeds = await BreedRequester.requestBreedsSyncWithoutInjection() {

print("Breed count using synchronous URLSession.data without injection: \(breeds.count)")

} else {

fatalError("Synchronous breed-fetching without injection failed.")

}

}

This invocation shows the no-callback value proposition of async/await. This implementation, however, shares the three drawbacks described above.

Injecting URLSession and URL for Fun and Profit

The cause of problems 1 and 2 (“may not exist” and “slow and flaky”) in the implementations above is their explicit dependency on URLSession.shared. That is, those implementations reach out for URLSession.shared, precluding any possibility of using some other variant of URLSession over which the client developer has control. URLSession.shared attempts to use the networking stack and the device’s radios (Wi-Fi or cellular) to reach out to a real backend at the URL specified. But, as noted above, that backend may not exist during early phases of development. I encountered this situation in a previous jobby-job, where backend and client development of new features was sometimes concurrent. Even if the backend exists, communicating with it via radio is slow and failure-prone, particularly in the context of a unit-test suite with thousands of tests.

The cause of problem 3 (“no exercise of the no-data or error cases”) in the implementations above is their explicit dependency on a specific URL: https://raceconditionsoftware.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/CatFancy/breeds.json. Assuming, as one would likely do, that the backend works as intended, that backend returns valid breed data. That backend doesn’t ordinarily return an error or no breeds. But without a response of an error or no breeds, the developer can’t develop the portion of the UI that handles these states.1 Here is an example of the sort of error UI that might be appropriate.

The solution to all three problems is dependency injection. I have discussed this concept elsewhere, but I define it here as “providing dependencies to functions that rely on them rather than having those functions initialize or grab those dependencies on their own behalves”. The nuts and bolts of providing those dependencies to a consuming function constitute a meaty topic, but I’ve got you covered.

That said, the particular dependency-injection technique used is unimportant for the purpose of solving the problems described in this post. CatFancy uses The World. For the sake of simplicity, this post will use method injection. A framework like Swinject is another solid choice. The key is to use some sort of dependency injection for the URL and URLSession.

Injection of these two dependencies solves the three problems.

Injecting a stub URLSession, rather than relying on URLSession.shared, solves problems 1 and 2 (“may not exist” and “slow and flaky”). An injected URLSession can grab data directly from the app bundle, bypassing the networking stack and the device’s radios entirely. This bundle access is fast and reliable.

Injecting an arbitrary URL, rather than relying on the URL at which data is expected to be found in production, solves problem 3 (“no exercise of the no-data or error cases”). In the happy path, the ordinary URL can be injected. But there can be alternate URLs for an error or no data. There can even be an extra URL for data that the backend doesn’t provide but that is helpful for exercising the UI. I used this extra URL in a coding challenge where the provided URL accessed so little data that all rows fit into one screen, with no scrolling of the enclosing UITableView. The extra URL had more data, enabling exercise of the app’s scrolling behavior.

Implementation

Enabling injection of the stub URLSession and of arbitrary URLs involves the following steps.

Making URLs Flexible

As described above, there need to be multiple URL variants for every endpoint, for example one featuring cat breeds expected to be accessed. The number and nature of the variants depend on the use case, but these are four variants I might implement for an app that retrieves a JSON file containing fourteen cat breeds from an endpoint and then displays those cat breeds in its UI:

standard: This is the actualURLof the endpoint. Assuming the backend works as expected, using thisURLshould result in the UI displaying fourteen cat breeds.empty: This is theURLof an imaginary endpoint that returns a JSON file containing an empty array of cat breeds. This should trigger the no-data error state in the UI.malformed: This is theURLof an imaginary endpoint that returns malformed JSON. This should trigger the bad-response error state in the UI.with_more: This is theURLof an imaginary endpoint that returns a JSON file with nineteen cat breeds. The UI should display these nineteen breeds.

Here is the representation of those four URLs in code:

enum BreedsURL: String, CaseIterable {

case standard

case empty

case malformed

case withMore

var url: URL {

let standardURLString = "https://raceconditionsoftware.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/CatFancy/breeds.json"

let emptyURLString = "https://raceconditionsoftware.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/CatFancy/breeds_empty.json"

let malformedURLString = "https://raceconditionsoftware.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/CatFancy/breeds_malformed.json"

let withMoreURLString = "https://raceconditionsoftware.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/CatFancy/breeds_with_more.json"

let urlString: String

switch self {

case .standard:

urlString = standardURLString

case .empty:

urlString = emptyURLString

case .malformed:

urlString = malformedURLString

case .withMore:

urlString = withMoreURLString

}

if let url = URL(string: urlString) {

return url

} else {

fatalError("Could not initialize URL from \(urlString).")

}

}

}

Adding Data to the App Bundle

JSON files containing no data, extra data, or malformed JSON don’t ordinarily exist at a typical endpoint. A JSON file containing expected data does exist at a typical endpoint, assuming that the endpoint has been implemented. But the goal of dependency injection, in this case, is to avoid reliance on any particular endpoint. For the four JSON files to be available, even in the absence of a network call, those JSON files must be in the app bundle. In the cat-breed app, this means adding the following four files to the bundle: breeds.json, breeds_empty.json, breeds_malformed.json, and breeds_with_more.json.

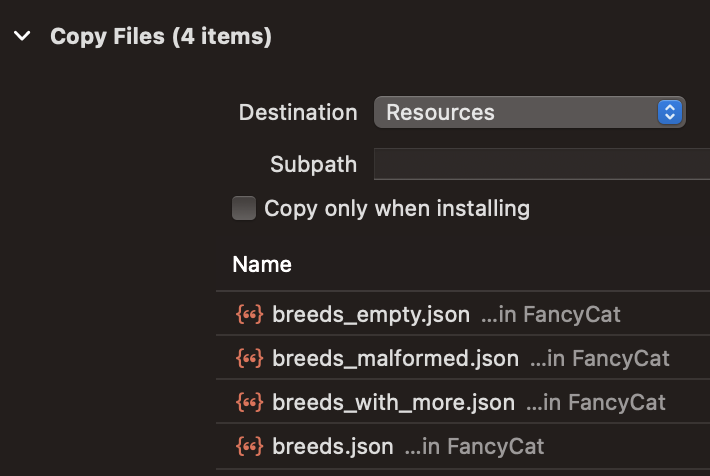

Caveat lector: adding files to the project doesn’t cause those files to be available in the app bundle, at least in a command-line tool like FancyCat. I added a build phase to copy those files to the app bundle, as shown here:

Implementing the Stub URLSession and URLProtocol Subclass

Recall the goal of creating an injectable URLSession that can potentially replace use of URLSession.shared. In industry parlance, this object is a stub, which Ibrahima Ciss defines as an object that “[p]rovides hard-coded answers to the calls performed during [a] test”. stubSession is a good name for this injectable URLSession. Following the Hudson example, I recommend implementing stubSession as a static var on URLSession. Here is that implementation, followed by explanatory comments.

extension URLSession {

static var didProcessURLs = false

static var stubSession: URLSession {

// 1

if !didProcessURLs {

BreedsURL.allCases.forEach {

if let path = Bundle.main.path(forResource: $0.url.lastPathComponent, ofType: nil) {

do {

let data = try Data(contentsOf: URL(fileURLWithPath: path))

URLProtocolStub.urlDataDict[$0.url] = data

} catch {

fatalError("Unable to load mock JSON data for URL \($0.url).")

}

}

}

didProcessURLs = true

}

// 2

let config = URLSessionConfiguration.ephemeral

config.protocolClasses = [URLProtocolStub.self]

return URLSession(configuration: config)

}

}

As promised, here are the explanatory comments.

1. For the injection to work, there needs to be a mapping between URLs and files in the app bundle. The first access of stubSession is a natural place for this to happen. By way of example, in CatFancy and FancyCat, the URL https://raceconditionsoftware.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/CatFancy/breeds_with_more.json is mapped to the app-bundle file breeds_with_more.json.

2. Recall that the URLSession stub, which must ultimately call the URLSession initializer, requires a URLSessionConfiguration, which is used “to configure the timeout values, caching policies, connection requirements, and other types of information that you intend to use with your URLSession object.” In section // 2 of the code above, a URLSessionConfiguration is initialized and configured with a URLProtocol subclass, shown below. This URLSessionConfiguration is then used to initialize the stub URLSession.

Here is the implementation of that URLProtocol subclass, followed by explanatory comments.

class URLProtocolStub: URLProtocol {

// 1

static var urlDataDict: [URL: Data] = [:]

// 2

override class func canInit(with request: URLRequest) -> Bool {

true

}

// 2

override class func canonicalRequest(for request: URLRequest) -> URLRequest {

request

}

// 2

override func startLoading() {

if

let url = request.url,

let data = URLProtocolStub.urlDataDict[url]

{

client?.urlProtocol(self, didReceive: URLResponse(), cacheStoragePolicy: .notAllowed)

client?.urlProtocol(self, didLoad: data)

} else {

client?.urlProtocol(self, didFailWithError: LoadingError.loadFailed)

}

client?.urlProtocolDidFinishLoading(self)

}

// 2

override func stopLoading() {}

// 3

enum LoadingError: Error {

case loadFailed

}

}

As promised, here are the explanatory comments.

1. This Dictionary contains mappings between URLs and Datas from the app bundle.

2. Although URLProtocol is technically a class, it acts like a protocol in that it represents a contract with methods for subclassers to implement. These implementations are largely boilerplate. The interesting function is startLoading(), which uses the dictionary defined in section // 1 to return data corresponding to the URL specified. In my implementation, startLoading() succeeds for every valid URL, but one could imagine enhancing this function to return Errors in certain scenarios, for testing purposes. 🐬 As Jon Shier suggested by way of feedback to this post, one could “enhance [the] URLProtocol [implementation] to allow delayed responses”, enabling more-realistic testing.

3. This enum could facilitate returning Errors in certain scenarios.

Injection in Practice

The implementations above enable injection of a URLSession and of a URL, solving problems 1 and 2, and 3: “may not exist”, “slow and flaky”, and “no exercise of the no-data or error cases”.

Here is the invocation of the classic URLSession.dataTask with dependency injection. This invocation involves neither a radio nor a networking stack.

BreedRequester.requestBreedsClassicWithInjection(session: URLSession.stubSession, url: BreedsURL.standard.url) { breeds in

if let breeds {

print("Breed count using classic URLSession.dataTask with injection: \(breeds.count)")

} else {

fatalError("Classic breed-fetching with injection failed.")

}

}

The first line of that snippet uses BreedsURL.standard, but use of .empty, .malformed, or .withMore would trigger the no-data error state, bad-response error state, and extra-data success state, respectively.

Here is the invocation of async URLSession.data. This invocation also involves neither a radio nor a networking stack.

Task {

if let breeds = await BreedRequester.requestBreedsSyncWithInjection(url: BreedsURL.standard.url, session: URLSession.stubSession) {

print("Breed count using synchronous URLSession.data with injection: \(breeds.count)")

} else {

fatalError("Synchronous breed-fetching with injection failed.")

}

}

The second line of that snippet uses BreedsURL.standard, but use of .empty, .malformed, or .withMore would trigger the no-data error data, bad-response error state, and extra-data success state, respectively.

In both invocations, use of URLSession.shared rather than URLSession.stubSession, for example during ordinary use of an app, would trigger use of the networking stack and of the device’s radios.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Paul Hudson for introducing me to the concept of a stub URLSession and for providing me with an implementation of one. I hope that this post has provided additional value to readers by introducing them to the benefits of an injected URL and by providing readers with an implementation of URLProtocol.startLoading() whose addition of the lines below fixed a crash I ran into while using async/await, which was unavailable at the time Mr. Hudson wrote his article.

} else {

client?.urlProtocol(self, didFailWithError: LoadingError.loadFailed)

}

Endnote

-

Strictly speaking, the preceding statement is untrue. Here are two ways that error UI could be developed. First, the developer could modify the code to simulate an error response without performing an actual API call. The disadvantage of this approach is that it differs from actual operation of an app, so the developer would wonder whether the error UI is actually triggered in production when expected. Second, the developer could use an app like Charles Proxy to intercept the API call and return an error message or no data. This second approach has two disadvantages. First, Charles Proxy has a formidable learning curve. By my count, the app has, on launch, eleven buttons, seven tabs, eight menus, and eighty-four menu items. Second, configuration of Charles Proxy is tricky, particularly in a locked-down corporate IT environment. To this end, at a previous employer, I wrestled with multiple Confluence pages, and I still had to ask for help, which was, thank goodness, readily available. ↩