Dependency injection makes unit testing possible and development easier. This post describes the process of preparing an app for dependency injection, as well as implementing three approaches to dependency injection: constructor injection, Swinject, and The World.

Needle Image by Needpix, Licensed Under Creative Commons Zero

Definition

This post is about implementing dependency injection, but before I dive into the nuts and bolts, likely not from a great height, I would like to provide a definition to readers who are unfamiliar with dependency injection. Here you go:

Dependency injection is the practice of taking away from objects the job of acquiring their dependencies. A dependency is an object that another object relies on to achieve its business purpose.

Although this definition is correct, it does not convey the value proposition of dependency injection. I consider value propositions key to understanding software-development concepts, and I therefore find this definition incomplete. I will remedy this by describing dependency injection’s value proposition or, in less jargony terms, the problem that dependency injection solves.

Value Proposition

Imagine a struct whose purpose is to turn a String like 5000 into a String formatted as currency, $5,000.00. Here is an implementation:

struct SimpleCurrencyFormatter {

private let formatter: NumberFormatter

init() {

formatter = NumberFormatter()

formatter.usesGroupingSeparator = true

formatter.numberStyle = .currency

}

func formatCurrency(string: String) -> String? {

guard let doubleValue = Double(string) else {

return nil

}

return formatter.string(from: NSNumber(value: doubleValue))

}

}

Here is an example use of SimpleCurrencyFormatter:

let errorString = "ERROR"

let rawCurrencyString = "5000"

let simpleCurrencyFormatter = SimpleCurrencyFormatter()

print(simpleCurrencyFormatter.formatCurrency(string: rawCurrencyString) ?? errorString)

As Jon Reid observed, “[a] robust suite of unit tests acts as a safety harness, giving you courage to make bold changes.” Desiring this benefit, I would indubitably unit test SimpleCurrencyFormatter were I to use it in production. Here is a unit test:

class SimpleCurrencyFormatterTests: XCTestCase {

func testSimpleCurrencyFormatter() {

let rawCurrency = "5000"

let simpleCurrencyFormatter = SimpleCurrencyFormatter()

guard let formattedCurrency = simpleCurrencyFormatter.formatCurrency(string: rawCurrency) else {

XCTFail("formattedCurrency was nil.")

return

}

XCTAssertEqual(formattedCurrency, "$5,000.00")

}

}

Although this unit test works on my laptop, there is a problem. SimpleCurrencyFormatter is responsible for acquiring a key dependency, the Locale, an object that “encapsulates information about linguistic, cultural, and technological conventions and standards”, in this case number-and-currency formatting. Because SimpleCurrencyFormatter specifies no Locale for its NumberFormatter, SimpleCurrencyFormatter chooses the default Locale for NumberFormatter, which, in my case, is the United Statesian Locale. But other developers have different Locales. A developer whose locale is French would see the unit test fail with this error: XCTAssertEqual failed: ("€5 000,00") is not equal to ("$5,000.00")

Dependency injection, specifically taking away from SimpleCurrencyFormatter the job of acquiring its Locale dependency, solves this problem. Consider the following implementation:

struct BetterCurrencyFormatter {

private let formatter: NumberFormatter

init(locale: Locale) {

formatter = NumberFormatter()

formatter.locale = locale

formatter.usesGroupingSeparator = true

formatter.numberStyle = .currency

}

func formatCurrency(string: String) -> String? {

guard let doubleValue = Double(string) else {

return nil

}

return formatter.string(from: NSNumber(value: doubleValue))

}

}

The following unit tests test this alternate implementation and are unaffected by developer Locale:

class BetterCurrencyFormatterTests: XCTestCase {

func testBritishCurrencyFormatter() {

let rawCurrencyString = "5000"

let localeIdentifier = "en_GB"

let betterCurrencyFormatter = BetterCurrencyFormatter(locale: Locale(identifier: localeIdentifier))

guard let formattedCurrency = betterCurrencyFormatter.formatCurrency(string: rawCurrency) else {

XCTFail("formattedCurrency was nil.")

return

}

XCTAssertEqual(formattedCurrency, "£5,000.00")

}

func testFrenchCurrencyFormatter() {

let rawCurrencyString = "5000"

let localeIdentifier = "fr_FR"

let betterCurrencyFormatter = BetterCurrencyFormatter(locale: Locale(identifier: localeIdentifier))

guard let formattedCurrency = betterCurrencyFormatter.formatCurrency(string: rawCurrency) else {

XCTFail("formattedCurrency was nil.")

return

}

XCTAssertEqual(formattedCurrency, "5 000,00 €")

}

}

In this implementation,1 the unit tests inject Locales into BetterCurrencyFormatter, making the developer’s Locale irrelevant. Even better, the injection of Locale allows testing multiple Locales, en_GB and fr_FR. Before injection, only the default Locale, in my case en_US, was testable. This application of dependency injection demonstrates a key value proposition of that practice: making objects easier to test.

Because the value proposition is key to understanding dependency injection, I propose the following amended definition of dependency injection:

Dependency injection is the practice of taking away from objects the job of acquiring their dependencies, making those objects more easily testable. A dependency is an object that another object relies on to achieve its business purpose.

Side Effects

The definition above is better, but it’s still incomplete.

Consider an app, Conjugar, that quizzes users on Spanish-verb conjugation. After Conjugar’s 2017 release and for almost two years, at the end of every quiz, Quiz, the object representing a quiz, ran the following code to report the user’s score to Game Center, Apple’s global game-leaderboard service:

GameCenter.shared.reportScore(score)

In my initial implementation of Conjugar, GameCenter.shared was a singleton that wrapped Apple’s GameKit framework, which exposes Game Center functionality, including the global leaderboard. This code in Quiz caused a problem for unit testing. Finishing a quiz in a unit test caused the side effect of that unit test’s score being reported to Game Center. This side effect was undesirable because the intent of the Game Center leaderboard is to show scores achieved by humans, not by unit tests.2 Injecting a testing implementation like the one below, which has no undesirable side effects, solves this problem and therefore constitutes, I argue, part of dependency injection’s value proposition.

class TestGameCenter: GameCenterable {

var isAuthenticated: Bool

init(isAuthenticated: Bool = false) {

self.isAuthenticated = isAuthenticated

}

func authenticate(analyticsService: AnalyticsServiceable?, completion: ((Bool) -> Void)?) {

if !isAuthenticated {

isAuthenticated = true

completion?(true)

} else {

completion?(false)

}

}

func reportScore(_ score: Int) {

print("Pretending to report score \(score).")

}

func showLeaderboard() {

print("Pretending to show leaderboard.")

}

}

In light of dependency injection’s potential rôle in preventing undesirable side effects during testing, I propose the following amended definition:

Dependency injection is the practice of taking away from objects the job of acquiring their dependencies, making those objects more easily testable, and wrapping potentially undesirable side effects in protocols so that those side effects can be avoided when appropriate. A dependency is an object that another object relies on to achieve its business purpose. A side effect is change that persists beyond the lifespan of an object that causes the side effect.

Dependencies and side effects are so intimately linked by their joint participation in the dependency-injection value proposition that I have invented a term, dependeffect, to encompass both, and I will use this term in the rest of this blog post.

Preparing for Dependency Injection

I now turn to preparing for dependency injection, which has three steps: identifying dependeffects, identifying dependency-injection scenarios, and making dependeffect objects injectable.

Identifying Dependeffects

An app that is not well unit-tested, for example Conjugar until early 2019, is likely to have many objects that are difficult to test because of dependencies, as well as many side effects that are undesirable in the unit- and UI-testing contexts. As discussed above, dependency injection addresses both dependencies and side effects. The first step in implementing dependency injection is identifying these dependeffects.

Some time ago, I wrote an arguably prolix blog post on this step, but, to summarize, the process involves asking, for each object in the app for which unit tests are desirable, the following questions:

What are the dependencies, implicit or otherwise, of this object?

What potentially undesirable side effects does use of this object cause?

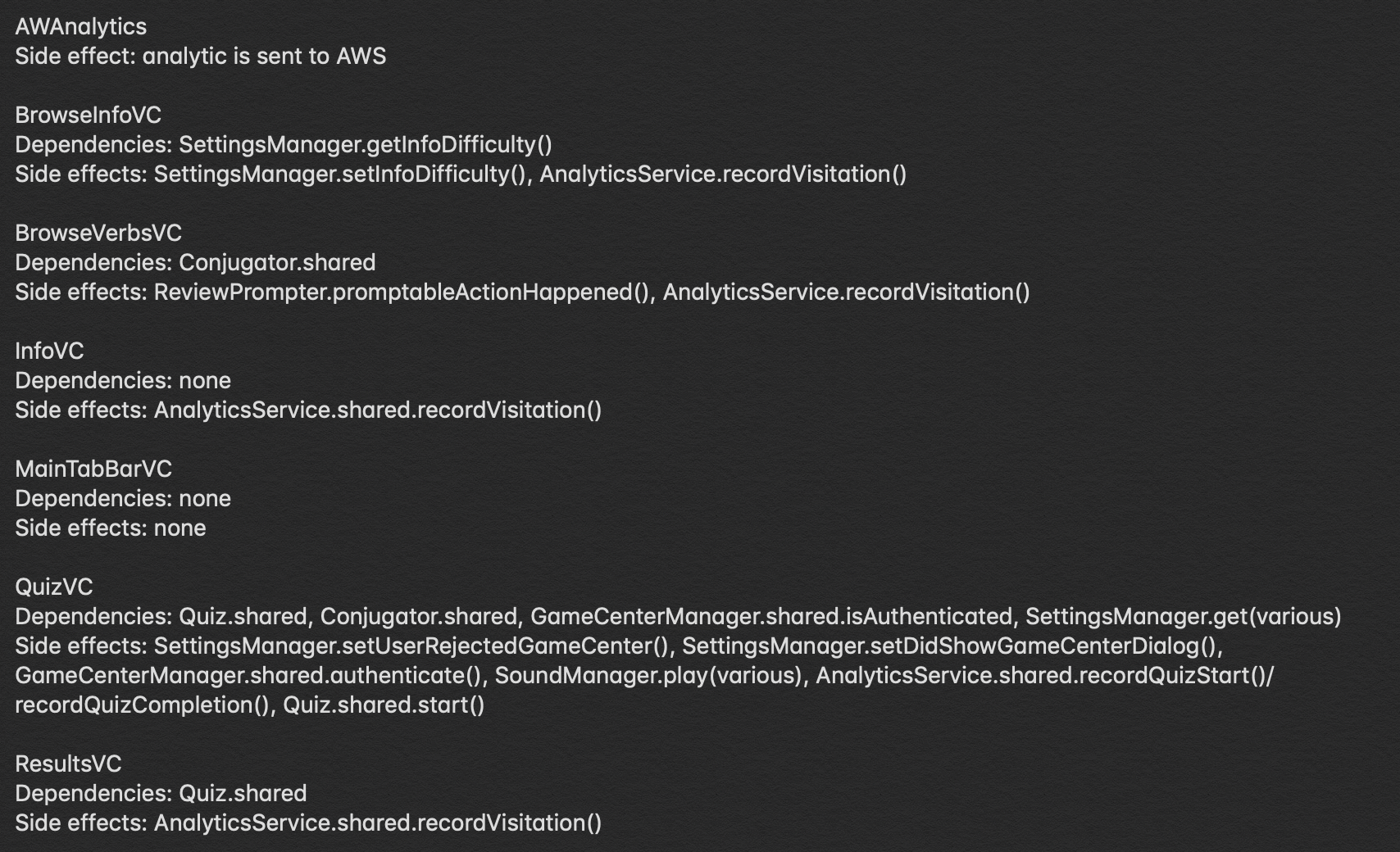

The end result of this investigation (or “audit”) is a list of objects and their dependeffects. This audit is both tedious, because it touches every source file in the app, and highly app-specific. By way of example, I reproduce here a portion of Conjugar’s audit.

Audit of Conjugar's Dependeffects

For three reasons, I recommend auditing the entire app for dependeffects rather than auditing just one object and implementing dependency injection for it.

- If unit tests are a high priority, unit tests can be immediately implemented for objects that lack dependeffects, representing a quick win for code quality.

- Considering how all objects, not just one object, use specific dependencies and trigger specific side effects promotes more-complete implementations of dependency injection for those dependeffects. For example, I found, during Conjugar’s audit, that objects had diverse requirements for the

Settingsobject that I was using to retrieve and store user preferences. I implemented dependency injection for settings in a manner that satisfied all requirements. - Implementing dependency injection to make one object testable can be daunting. For example,

QuizVC, the view controller representing Conjugar’s quiz screen, had twenty-two dependeffect usages. But after I completed the audit and readied Conjugar for dependency injection, a process described below, unit testingQuizVCand all other objects was easy. One measure of this ease is the fact that I was able to listen to podcasts during the process of modifying objects to use dependency injection, something I cannot do when a task, for example adding this parenthetical aside to this sentence, requires my undivided attention.

From the list of objects and their dependeffects, compile a master list of dependeffects. To give the reader a sense of what these look like, I present Conjugar’s dependeffects here.

Settings: This was a dependency in thatSettingsaffected behavior of the app. For example, thedifficultysetting determined what verb tenses Conjugar included in quizzes. The greater the difficulty, the more tenses quizzed.Settingsalso potentially had side effects because, whenUserDefaultsbackedSettings, as was the case in my initial implementation, changes toSettingscaused persistent changes to the contents ofUserDefaults.Analytics: This object had side effects because, in my initial implementation, firing an analytic, for example when a user visited a particular screen or completed a quiz, caused the analytic to be sent to Conjugar’s AWS Pinpoint analytics backend.ReviewPrompter: This object, whose purpose is to prompt the user for a review at appropriate intervals, had the potential side effect of requesting a review by callingSKStoreReviewController.requestReview(). I discussedReviewPrompterextensively in an earlier post.GameCenter: This object was a dependency because of its propertyisAuthenticated, which determined whether Conjugar’s UI showed a button that triggered Game Center authentication. This object had the potential side effects of reporting scores to Game Center and showing the global leaderboard after completion of a quiz.Quiz: This object was a dependency because the output of Swift’s random-number generator determined the verbs, tenses, and person-numbers quizzed. This randomness was appropriate for real quizzes but problematic, in terms of repeatability, for unit and UI tests. As Tim Ottinger and Jeff Langr observed, “[y]ou should obtain the same results every time you run a test.”URLSession: One feature of Conjugar is an indication, on the settings screen, of how many users have rated the current version of Conjugar. During ordinary operation, Conjugar uses a vanillaURLSessionto retrieve the ratings count. ThisURLSessionwas a dependency because it determined, in part, the contents of the settings screen, and I have no control over the ratings count returned by the Apple backend.

What constitutes an undesirable side effect is, in some cases, a judgment call. Conjugar has a class, SoundPlayer, for playing sounds. One use of SoundPlayer is in QuizVC, which causes SoundPlayer to play a chime sound when the user correctly inputs a conjugation. This audible sound is a potentially undesirable side effect of using SoundPlayer because, in a UI test with 300 correct conjugations, the repeated chime sound might become annoying. But I still enjoy the chime, so I did not bother treating SoundPlayer as having a side effect.

Identifying Dependency-Injection Scenarios

The next step is identifying dependency-injection scenarios and which dependeffects are appropriate for each.3 Here is the analysis for Conjugar.

- On device: Because I created Conjugar to run on iPhones, the existing dependeffects were appropriate for this scenario. For example, a user would want preferences to be read from and saved to

UserDefaults. A user’s quiz score should be reported to GameCenter. A user should be prompted for a review at the appropriate interval. A user should see the number of ratings for the current version on the settings screen. User activity should trigger appropriate analytics. Quizzes should contain random assortments of tenses, verbs, and person-numbers. - Simulator: This scenario applies during development. As in the on-device scenario, preferences should be read from and saved to

UserDefaults, and quizzes should contain random assortments of tenses, verbs, and person-numbers. But quiz scores should not be reported to Game Center. I, the developer, should not be prompted to review my own app because I am completely biased.URLSessionshould not get the actual ratings count because that network request is potentially unreliable. My development activities should not trigger analytics because I presumably know how I’m using my own app and do not want my analytics co-mingled with user analytics. - UI testing: This scenario is similar to the simulator scenario, but storing settings in

UserDefaultsis inappropriate because UI-test runs should not affect each other, as they would if settings were persisted toUserDefaults. Instead, settings should be stored in memory and settable via launch arguments to the UI tests. In order to make UI tests repeatable, each quiz should use the same set of verbs, tenses, and person-numbers, not a random assortment. - Unit testing: This scenario is similar to the UI-testing scenario, but settings should be settable in unit tests rather than via launch arguments because dependeffect requirements vary by unit test. For example, a unit test that tests a quiz containing difficult verb tenses should include a difficulty setting.

The starting point for all forms of dependency injection is in AppDelegate.didFinishLaunchingWithOptions() because that is the earliest point at which the app can determine which dependency-injection scenario and therefore which dependeffects are appropriate.

A UI test can use dependency injection as follows:

let enableUITestingArgument = "enable-ui-testing"

XCUIApplication().launchArguments = [enableUITestingArgument]

AppDelegate.didFinishLaunchingWithOptions() detects this argument, and therefore the UI-testing scenario, as follows:4

let enableUITestingArgument = "enable-ui-testing"

if CommandLine.arguments.contains(enableUITestingArgument) {

// Create UI-testing dependeffects.

}

Detecting the device-or-simulator scenarios is more straightforward:

#if targetEnvironment(simulator)

// Create simulator dependeffects.

#else

// Create device dependeffects.

#endif

Making Dependeffect Objects Injectable

There are three techniques for making dependeffect objects injectable.

One is to put the externally visible functions and properties of the dependeffect into a protocol. Then make a test object that conforms to this protocol. Then indicate conformance to the protocol in the production object, which should already exist in a working app.

I discussed this process in my earlier post on dependency injection, but I’ll summarize the outcome of it for ReviewPrompter, which I had identified as having a side effect because of its possible behavior of prompting the user for a review and as having a dependency on the date of last review-prompting stored in UserDefaults.

I created the following protocol, which contains the one externally facing function of ReviewPrompter:

protocol ReviewPromptable {

func promptableActionHappened()

}

For context, Conjugar calls promptableActionHappened() on completion of a quiz, reasoning that a user who has completed a quiz is more likely to rate or review the app.

I then created a test object that conforms to ReviewPromptable in a side-effect-free manner:

class TestReviewPrompter: ReviewPromptable {

func promptableActionHappened() {}

}

I then added : ReviewPromptable to ReviewPrompter’s declaration to indicate ReviewPrompter’s conformance to the ReviewPromptable protocol.

The second technique for making a dependeffect object injectable is to add a parameter to its initializer that addresses the dependency or side effect. Here are three examples of this technique:

- I added to

Quiz’s initializer a parametershouldShuffle: Bool. I then modifiedQuizto not use the random-number generator when this parameter istrue, potentially removing the random-number-generator dependency for UI- and unit-testing clients. - As the ever-attentive reader likely remembers, I used this technique in

BettterCurrencyFormatter, earlier in this blog post, by adding aLocaleparameter to the initializer. - I added to

Settings’s initializer a parametergetterSetter: GetterSetter.GetterSetteris a protocol for saving and retrieving values.GetterSetterhas two conforming types:DictionaryGetterSetter, an implementation that, because it uses aDictionaryfor storage, has no side effects or dependencies other than what the client chooses to put in theDictionary, andUserDefaultsGetterSetter, an implementation that, because it usesUserDefaultsfor storage, has the expectedUserDefaultsdependency and side-effects.

The third technique for making a dependeffect object injectable is specific to URLSession and is beyond the scope of this post. Paul Hudson has described this technique, which Conjugar uses for its URLSession dependency.

Injecting Dependeffects: Three Techniques

An app that has undergone the process described above is ready for dependency injection. There are many ways to inject dependeffects, but I describe three here: constructor injection, Swinject, and The World.

Constructor Injection

Constructor injection is the process of passing dependeffects to objects that need them via their initializers. The word “constructor”, perhaps alien to some Swift-and-Objective-C developers, is a legacy of the Java community’s contributions to dependency injection. A Java constructor equates to a Swift initializer.

As stated above, the starting point for all forms of dependency injection is in AppDelegate.didFinishLaunchingWithOptions(). For constructor injection, the approach is to create dependeffects that are appropriate for the current scenario and pass them to the top-level object in the app via its initializer. In Conjugar, the top-level object is mainTabBarVC, an instance of MainTabBarVC. Passing the dependeffects in the UI-testing scenario looks like this:

mainTabBarVC = MainTabBarVC(settings: settings, quiz: Quiz(settings: settings, gameCenter: TestGameCenter(), shouldShuffle: false), analyticsService: TestAnalyticsService(), reviewPrompter: TestReviewPrompter(), gameCenter: TestGameCenter(), session: stubSession)

The top-level object, in turns, passes appropriate dependeffects to other objects via their initializers. Here is how Conjugar’s mainTabBarVC passes dependeffects to quizVC, which is the view controller for a quiz:

QuizVC(settings: settings, quiz: quiz, analyticsService: analyticsService, gameCenter: gameCenter)

Objects that need dependeffects have properties to hold those dependeffects and use those dependeffects when appropriate. Here is an abbreviated version of QuizVC that demonstrates this.

class QuizVC: UIViewController, ... {

private let settings: Settings

private let gameCenter: GameCenterable

...

init(settings: Settings, quiz: Quiz, analyticsService: AnalyticsServiceable, gameCenter: GameCenterable) { {

self.settings = settings

self.gameCenter = gameCenter

...

}

...

private func authenticate() {

if !gameCenter.isAuthenticated && settings.userRejectedGameCenter {

...

}

}

...

}

Compared to other dependency-injection techniques discussed in this blog post, the benefit of constructor injection is simplicity. If you know how to pass a parameter and how to prepare an app for dependency injection, you know how to do constructor injection. This simplicity caused me to use constructor injection in my initial crack at dependency injection in Conjugar.

One disadvantage of constructor injection is that it was incompatible with Interface Builder until the advent in Xcode 11 of IBSegueAction. This annotation permits use of constructor injection in the Interface Builder context, but it requires use of segues, which, as Paul Hudson observed, “force us into a specific application flow that stops us rearranging view controllers freely.”

A new iOS 13 API, instantiateViewController(identifier:creator:), permits constructor injection with Interface Builder and without segues but has unfortunately not been backported to earlier iOS versions.

Another disadvantage of constructor injection is that its use bloats parameter lists. As illustrated above, one object in a not-terribly-complicated app, Conjugar, has six parameters just for dependeffects!

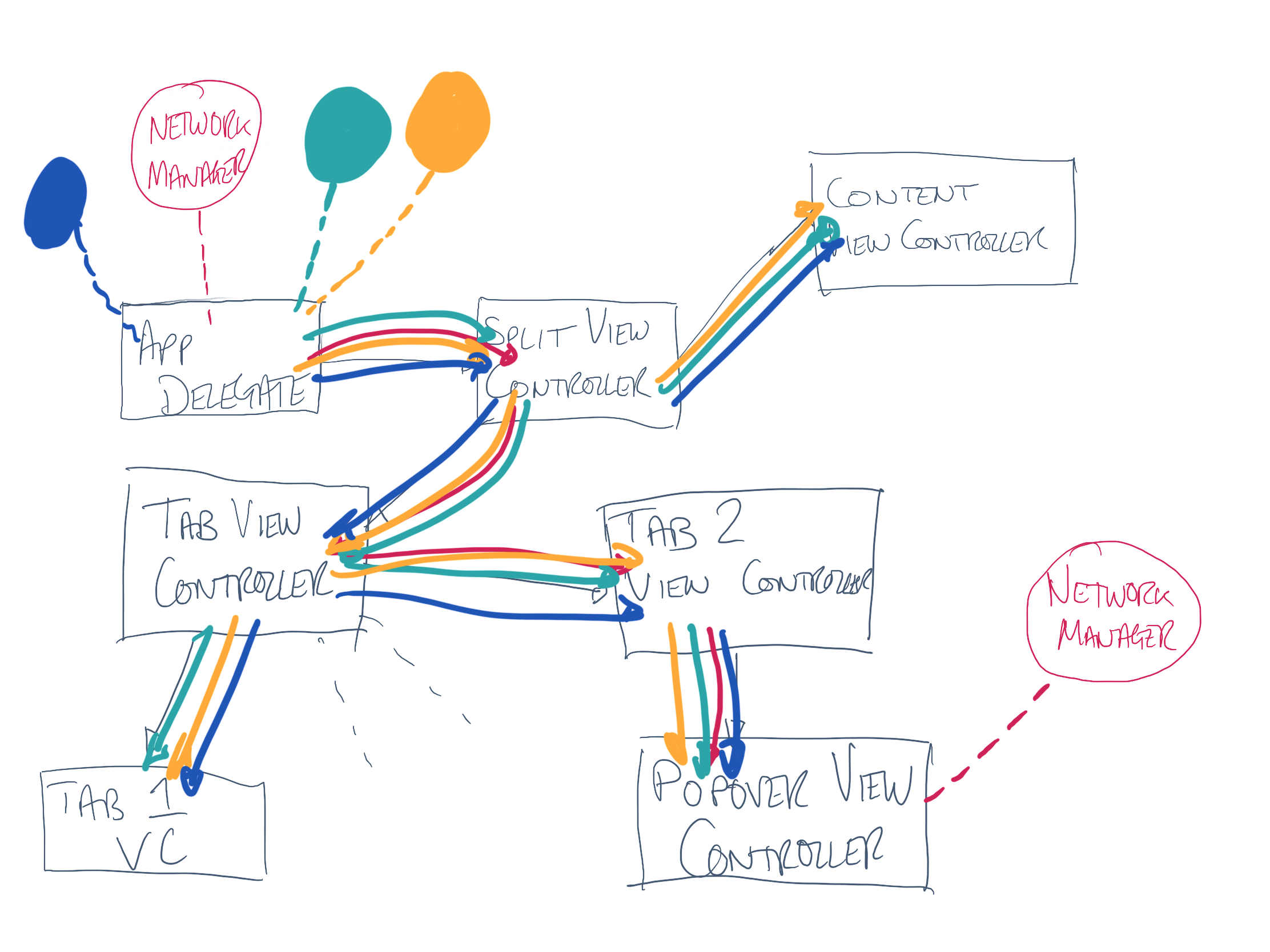

Passing dependeffects around an app creates a complicated web of parameters, as illustrated by Sam Davies in his talk DIY DI:

Objects Connected by Constructor Injection, Illustration by Sam Davies, Licensed under MIT

These dependeffect parameters obscure parameters that are more closely related to an object’s purpose, decreasing readability. Consider the signature of VerbVC, an object whose purpose is to show a screen with conjugations for a particular verb:

init(verb: String, settings: Settings, analyticsService: AnalyticsServiceable)

The verb parameter is central to this object’s purpose. The other two parameters are mere dependeffects. In the Swinject and The World implementations, dependeffects would not clutter the parameter list and would therefore not obscure the centrality of the verb parameter.

Branch constructor-injection of Conjugar’s repo uses constructor injection.

Swinject

“Swinject is a lightweight dependency injection framework for Swift.” The word “lightweight” is appropriate, in that the main Swinject project contained, as of mid-2019, 2,317 lines of Swift code and added a mere 300 KB to binary size.

Swinject’s documentation is excellent, and there are many other resources for learning about it, including this talk by Swinject creator Yoichi Tagaya, this tutorial by Gemma Barlow, and this blog post by Pierre Felgines.

Use of Swinject involves two steps:

- “First, register a service and component pair to a

Container, where the component is created by the registered closure as a factory.” - “Then get an instance of a service from the container”, a process called “resolution”.

As with constructor injection, AppDelegate.didFinishLaunchingWithOptions() is the place to initiate5 registration because that is the earliest point at which the app can determine which dependency-injection scenario and therefore which dependeffects are appropriate. In Swinject sample code, AppDelegate owns the container, but, for two reasons, I believe that the container should be global.

- Keeping the container in

AppDelegateviolates separation of concerns. That is, the job ofAppDelegateis responding to app-lifecycle events, not owning a dependency container. - If any object other than

AppDelegateneeds to use the container, that object must first get a reference toAppDelegate, adding visual clutter. In an issue I created on the Swinject repo, two commenters, Jakub Vano and Derek Clarkson, agreed that the container should be global.

In Conjugar, the global container, GlobalContainer, has static computed properties for every dependeffect. Here is the settings property:

private static let notRegisteredMessage = "has not been registered."

...

static var settings: Settings {

if let settings = container.resolve(Settings.self) {

return settings

} else {

fatalError("\(Settings.self) \(notRegisteredMessage)")

}

}

AppDelegate.didFinishLaunchingWithOptions() calls functions like GlobalContainer.registerSimulatorDependencies() in order to register the appropriate service-and-component pairs.

Objects access the dependeffects through the computed properties of the global container, as shown in this example from Conjugar’s QuizVC:

private func authenticate() {

if !GlobalContainer.gameCenter.isAuthenticated && GlobalContainer.settings.userRejectedGameCenter {

...

}

}

Astute readers may notice that an attempt to access a computed property of GlobalContainer causes a crash when the dependeffect cannot be resolved, likely because it has not been registered. Unfortunately, Swinject’s resolve() function returns an Optional, so when I incorporated Swinject into a branch of Conjugar, I had two options: deal with Optional dependeffects or crash if they couldn’t be resolved. To avoid boilerplate, for example involving the guard keyword, I chose crashing. There is a subproject of Swinject, SwinjectAutoregistration, that resolves to non-Optionals, but the app still crashes if a dependeffect hasn’t been registered. For Conjugar’s use of Swinject, I preferred to keep the code causing this crash in my own codebase and avoid the SwinjectAutoregistration dependency.

The main disadvantage of Swinject, compared to the other two approaches discussed in this blog post, is that Swinject is a third-party dependency and therefore imposes risk: if development of Swinject ceases, any apps using it will either need to handle maintenance themselves or entirely remove Swinject. There is a strong case for third-party dependencies in domains like cryptography, where rolling one’s own solution is extremely difficult and error-prone. But as demonstrated in this blog post, rolling one’s own dependency-injection solution is simple, at least compared to cryptography.

A minor disadvantage of Swinject is that components (that is, concrete implementations of dependeffects) can’t have private initializers. This is not ideal for Conjugar and perhaps other apps because some objects, for example GameCenter, should not be directly initializable by clients. The reason, in GameCenter’s case, is that allowing clients to create multiple objects interacting with the Game Center backend could cause incorrect results. For example, if one GameCenter object undergoes the authentication process, the other GameCenter’s isAuthenticated property will still be false, which is semantically incorrect. This limitation of Swinject is, however, minor because there is a workaround. Clients can use the inObjectScope() function when registering a paired service type and component factory, permitting the component to be either recreated on each resolution or created just once and shared throughout the app. This latter usage would solve the GameCenter problem.

Notwithstanding these two disadvantages, Swinject has indicia of the sort of third-party dependency that I would be comfortable adopting. Documentation is extensive, and tutorials are plentiful. Swinject has no dependencies of its own. Help with Swinject is available on StackOverflow and on the issues page. When I created two issues asking about Swinject, folks provided quick, helpful answers. Swinject is small enough, 2,317 lines, that understanding the whole codebase is feasible. Swinject has benefitted from regular maintenance since its release in August, 2015.

The advantage of Swinject over The World and constructor injection is that Swinject provides certain features that the other techniques do not. I’ve already described object scopes. Another feature is that Swinject provides thread-safe access to containers via the synchronize() function. Swinject supports dependency injection in the storyboard context, an impressive feat. I strongly urge anyone considering dependency-injection options to read the Swinject documentation with the goal of deciding whether any of Swinject’s features are compelling.

The swinject branch of Conjugar’s repo uses Swinject.

The World

Point-Free created The World, a solution to the problems posed by dependeffects. Point-Free doesn’t use the term “dependency injection” to describe The World, reserving that term for constructor injection. But because The World addresses the same problems as dependency injection, I discuss The World here.

World is a struct that has properties for all dependeffects in the app. These properties are typically protocols describing functionality the apps needs or configurable objects. Here is a partial definition of World from Conjugar:

struct World {

// protocols

var analytics: AnalyticsServiceable

var reviewPrompter: ReviewPromptable

var gameCenter: GameCenterable

// configurable objects

var settings: Settings

var quiz: Quiz

var session: URLSession

...

}

World has static, computed properties for setting up dependeffects for the various scenarios. Here is the static, computed property for the on-device scenario:

static let device: World = {

let settings = Settings(getterSetter: UserDefaultsGetterSetter())

let gameCenter = GameCenter.shared

return World(

analytics: AWSAnalyticsService(),

reviewPrompter: ReviewPrompter(),

gameCenter: gameCenter,

settings: settings,

quiz: Quiz(settings: settings, gameCenter: gameCenter, shouldShuffle: true),

session: URLSession.shared

)

}()

AppDelegate.didFinishLaunchingWithOptions() or a unit test set a global instance of World, called Current, using the appropriate static, computed property. Here is how that looks for UI tests:

Current = World.uiTest(launchArguments: CommandLine.arguments)

From that point forward, clients access dependeffects through the Current instance. Here is an example from Conjugar’s QuizVC:

private func authenticate() {

if !Current.gameCenter.isAuthenticated && Current.settings.userRejectedGameCenter {

...

}

}

Mutation of Current in production could cause subtle and difficult-to-find bugs. Point-Free therefore recommends using a compiler directive to prevent mutation of Current in production, as shown here:

#if DEBUG

var Current = World()

#else

let Current = World()

#endif

This gives appropriate clients, for example unit tests, flexibility for mutating Current while maintaining production safety.

The Point-Free article introducing The World to the world describes benefits of The World, which I summarize as follows:

- There is less boilerplate compared to constructor injection. Objects needing dependeffects need not have properties to hold their dependeffects. Dependeffects need not be passed around the app, cluttering initializer parameter lists. This parameter-passing is problematic for constructor injection because one change to, or addition of, a dependeffect can have cascading effects on many files.

Currentprovides clarity of developer intent. For example, the presence ofCurrentinCurrent.gameCenter.isAuthenticatedmakes clear the developer’s intent to use a dependeffect,gameCenter, as opposed to a property that is specific toQuizVC. IfgameCenterwere a property, as it would be in the constructor-injection scenario, the codegameCenter.isAuthenticatedwould not announce to the reader thatgameCenteris a dependeffect.- Unlike constructor injection, The World is fully compatible with Interface Builder.

The disadvantage of The World is that singletons are controversial. As one StackOverflow answer with 432 upvotes says,

It’s rare that you need a singleton. The reason they’re bad is that they feel like a global[,] and they’re a fully paid up [sic] member of the GoF Design Patterns book. When you think you need a global, you’re probably making a terrible design mistake.

If minimizing controversy were my primary goal in choosing an approach to dependency injection, I would avoid The World. But it is not, and I would not. This is not to say that the perceptions of other developers play no rôle in my approach to software development. For example, for esthetic reasons, I would prefer, like Eric Allman, to put the opening brace (“{“) on its own line. But following the overwhelming preference of my software-development community, I put the opening brace at the end of the line beginning the relevant scope. That said, I find the technical benefits of The World, described in preceding paragraphs, more compelling than my esthetic preference for Allman-style brace placement.

The master branch of Conjugar’s repo uses The World.

Recommendations

Here are some recommendations for choosing a dependency-injection approach.

In a small app with few dependeffects, I recommend constructor injection. This use would be simpler than one involving Swinject and less controversial than one involving The World.

If business needs strongly militate in favor of one or more features of Swinject, I recommend Swinject. More generally, I recommend examining the feature sets of other dependency-injection frameworks, including Weaver, Typhoon, Cleanse, and Needle.

Otherwise, the clarity and reduction-of-boilerplate benefits of The World cause me to recommend that approach. Indeed, I am so convinced of The World’s benefits that Conjugar will use that approach going forward.

Colophon

I wrote much of this post on my laptop while riding Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), the San Francisco Bay Area’s light-rail system. BART is usually too crowded for me to get a seat. How did I use my laptop? I sat on a camping chair that I carry to and from my office.

Endnotes

-

I recognize that there is code duplication between the two unit tests. In production units tests, I would move the locale identifiers, raw

Stringss, and expectedStrings into tuples, an approach described here. ↩ -

I thank Stephen Celis for prompting me to consider the distinct implications of these scenarios. ↩

-

The repetition of the line

let enableUITestingArgument = "enable-ui-testing"illustrates one drawback of vanilla UI testing. Because UI tests have no access to any symbol in the app under test, strict adherence to the DRY principle is sometimes difficult. One solution in this case would be to putenableUITestingArgumentin a framework that can be shared by the app and UI-test targets, but this strikes me as overkill for my use case. I note that this challenge is present, to a lesser extent, in unit tests because they do not have access toprivatesymbols in the tested code.@testable importdoes give unit tests access tointernalsymbols. ↩ -

I say “initiate”, not “perform”, registration because I believe that performing the registration in

AppDelegatewould violate separation of concerns. The implementation of registration is unrelated toAppDelegate’s purpose of responding to app-lifecycle events. ↩