This post presents learnings from seven years of completing take-home coding challenges for iOS-developer jobs. If you, the reader, intend to complete one of these challenges in the future, I intend to help you succeed. A model coding-challenge solution accompanies this post.

Introduction

In 2015 and 2016, when I was an aspirant to the iOS-development industry, I completed six coding challenges while applying to jobs. Four of my six solutions resulted in my immediate rejection. I did get a full-time iOS-development job in late 2016. Because both of that job and of my independent study, my skill as an iOS developer greatly increased. In 2021 and 2022, I completed six additional coding challenges while applying to jobs. All six of my solutions were accepted. To the extent that I received feedback on those solutions, that feedback was extremely positive.1

I wish that I had known in 2015 what I know now. Because of what I didn’t know, the effort I put into those four unsuccessful coding-challenge solutions seemed, at the time, to have been in vain. But assuming that you, the reader, are an aspirant to the iOS-development industry or just someone who has faced repeated rejections after completing coding challenges, this post might help you experience more success on coding challenges than I did in 2015 and 2016. I wrote this post for you.

Here is a roadmap for the post, presented as a series of questions to which the post provides answers:

- What is a typical coding challenge?

- What are the keys to success on a coding challenge?

- What are the time limits on coding challenges?

- How should the candidate treat ambiguities or lacunae in coding-challenge requirements?

- What decisions go into implementing a coding-challenge solution?

- How should a potential iOS-job candidate prepare for coding challenges?

- Given this preparation, how should a candidate complete a coding challenge?

Varieties of Coding Challenges

There are as many possible variants of iOS-developer-job coding challenges as there are companies that screen potential iOS developers via coding challenges. That said, based on my experience, some generalizations are possible.

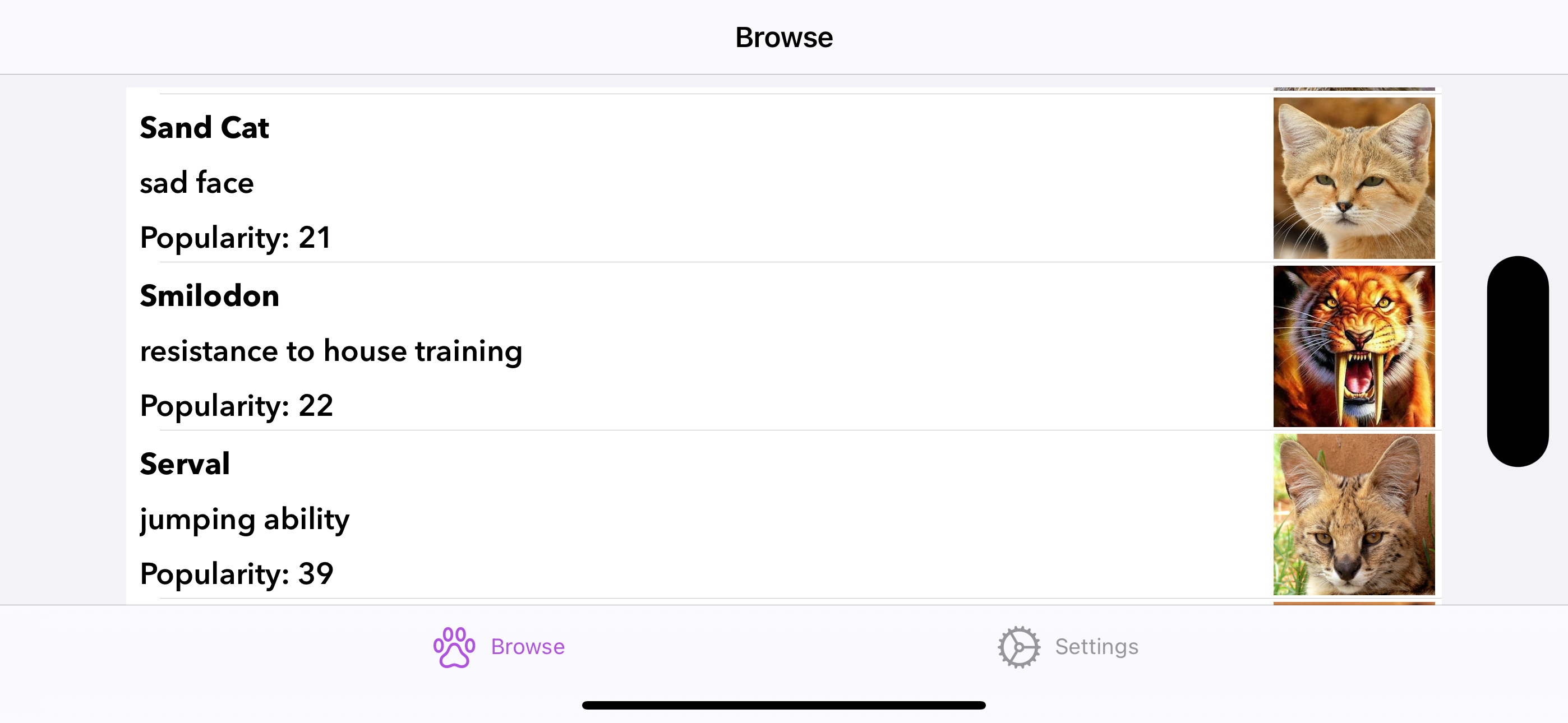

Eight of the twelve coding challenges I have done involve fetching JSON from an endpoint and allowing the user to browse this data in some sort of list, which I have interpreted as a UITableView.2

Here are some unusual coding challenges that deviated from the above pattern:

- One challenge involved fetching JSON from an endpoint and displaying data in a

UICollectionViewwith a custom layout. - One challenge involved fetching JSON from an endpoint, displaying data in a

UIPageViewController, and implementing an e-commerce-checkout flow. - One challenge involved fetching JSON from an endpoint, displaying data in various

UIViews, and implementing a quiz. - One challenge was a LeetCode-style problem that didn’t require an iOS app at all. (I made a command-line app.)

- One challenge included a starter project. I found this challenge more difficult because I couldn’t begin work on the challenge until I fully grokked the provided code, which took considerable time and effort.

I have seen the following requirements across many, though far from all, coding challenges:

- Allow the user to drill down on a row in the list and see more details on another screen.

- Fetch just an initial batch of JSON and then more when the user reaches the end of the list.

- Implement a specific UI design.

- Include unit tests.

- Handle error states, specifically empty-or-malformed JSON.

- Include a readme explaining design decisions.

- Use image URLs in the JSON to display images in the list and perhaps on a details screen. This requirement implies a requirement to implement image caching because

UITableViewperformance with images, in the absence of caching, is terrible.

With respect to external dependencies and clarifying questions, some challenges allowed them, some forbade them, and most didn’t mention them.

These observations suggest some steps towards preparing to complete coding challenges: get comfortable with UITableView, REST-endpoint access, JSON retrieval, JSON parsing via Codable, image display in UITableViews, and image caching.

Primary Key to Success: Unit Testing via Dependency Injection

Like I said in the introduction to this post, my success rate increased dramatically between, on the one hand, 2015-16 and, on the other, 2021-22. Reviewers reported, in response to solutions I completed for the second batch of coding challenges, that they found my unit-test coverage comprehensive and impressive. Because this response was so positive and nearly universal, I suspect that the lower success rate for my first batch resulted from the absence of unit tests in that batch.

Learning about unit testing and dependency injection, to the point that I was comfortable applying them in coding challenges, was a years-long journey. I read books by Jon Reid and Dominik Hauser on unit testing and dependency injection. I worked through the Ray Wenderlich tutorial. I blogged about dependency injection and preparing an app for it. I achieved comprehensive unit-test coverage for my Spanish-verb-conjugation app, Conjugar.

Other Success Factors

Aside from unit testing, certain other practices probably contributed to my successes on recent coding challenges.

I integrated SwiftLint. Reviewers might not have even noticed the .swiftlint.yml file or SwiftLint build phase. But SwiftLint always caught some style errors when I integrated it into coding challenges, for example extra blank lines between functions or missing spaces between if statements and {s. This code tidiness fostered, I suspect, a perception of attention to detail by reviewers.

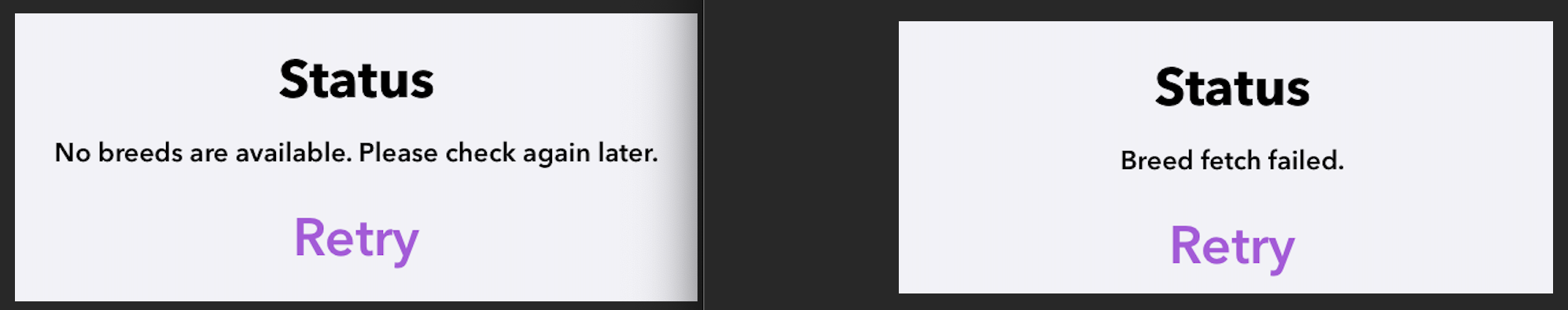

As noted above, some, but not all, coding challenges explicitly required handling error states, which I took to mean, in the context of a typical coding challenge, invalid-or-empty JSON. I handled those in every coding challenge, not just those with the requirement. Here are, for example, the error states in CatFancy, the app I implemented for this post:

Implementing error states even in coding challenges that didn’t require them had two benefits. First, the error-state handling signaled to challenge reviewers that I had worked on production-quality code, which does handle error states. A job candidate who has worked on production code in the past is well-equipped to work on the production code of a potential employer. Second, not having to decide whether to keep or remove error handling saved implementation time because my template app, exemplified, for the purpose of this post, by CatFancy, already handled error states, and affirmatively removing that logic would have taken additional time.

A final factor in my recent successes on coding challenges has been adherence to the single-responsibliity principle and to the related principle of separation of concerns. In the distant past, I did not always so adhere. For example, in my 2013 app Immigration, I put logic for communicating between view controllers in my UITabBarController subclass. The subclass was a God Object. This logic placement was convenient but severely limited my ability to unit test both the subclass and the view controllers.

Here are two examples of how my approach has changed both in my production code and in my coding challenges. I’ve taken away from view controllers two responsibilities they are sometimes given: conformance to UITableViewDelegate/UITableViewDataSource3 and navigation to other view controllers. Reviewers have reacted positively, I suspect, to my adherence to these two principles in coding challenges because the principles help prevent a production codebase from becoming an untestable, inscrutable bowl of spaghetti. In recent years, I have given reviewers no reason to fear spaghettification resulting from my addition to their teams.

Time Limits

“Time limit”, in the context of coding challenges, can have two distinct meanings. One, the challenge may present a certain number of hours as a suggestion. There is often language like “Don’t spend more than a few hours on this.” Two, the time limit may be strictly enforced. I’ve seen this enforcement take two forms. One company asked that I record my screen during the entire challenge. Another company had some engineers meet with me, they gave me the challenge, and then we met two hours later to discuss what I had completed.

The lengths of time limits, enforced or suggested, vary widely. On the two challenges I did with strict time limits, the limits were seventy-five minutes and two hours. I’ve seen suggested time limits as low as “a couple hours”. I’ve seen a suggestion of ten hours. Some coding challenges don’t mention time limits.

When the time limit is strictly enforced, there is no question as to how long to spend on a coding challenge. But what if the time limit is a suggestion, not enforced? There are competing interests. A job candidate may have a paying job and/or family obligations. A job candidate may be applying to multiple jobs, some with their own coding challenges to complete. The time available is always finite. But, on the other hand, there must be some correlation between the time spent on a coding challenge and the likelihood of success. A solution that a candidate spent an hour on must surely be less likely to be accepted than a solution that the same candidate spent forty hours on. Since the candidate’s overriding goal is to produce a successful solution, there is a strong incentive to spend the considerable time required to make a solution truly outstanding, not just to satisfy the bare requirements.

Because of these competing interests, I can’t tell you how long you should spend on a coding challenge. You may code faster or (less likely) more slowly than I do. Instead, I’ll describe how I have approached flexible time limits. I spent thirty hours on the first coding challenge I did in 2021, having leveled up my unit-testing and other skills. This level of effort seemed, and perhaps is, ridiculous, but I was able to reuse much of the code from that app in subsequent coding challenges, and I spent between six and fifteen hours on them, depending on the similarity of each challenge to those I had already completed. (The challenge that required a UICollectionViewLayout subclass took fifteen hours.) This range of hours of effort has worked well for me, and I’m therefore comfortable recommending it. Even my solution to the challenge with the strict two-hour time limit benefited from my previous experience, in that I was able to get a working, if imperfect, solution done in that time. Had I not done similar challenges in the past, I might have spent two hours just loading and parsing JSON.

Questions & Requirements

Upon receiving a coding challenge, I have sometimes felt the urge to pepper my point of contact with questions like the following:

Should I fully support VoiceOver? Should I internationalize? Is programmatic layout okay? What Xcode version should I use? Should I make distinct iPhone and iPad layouts? Should

go tobe considered harmful?

But for the most part, I have avoided asking questions before beginning work on a coding-challenge solution. In not asking questions, I have reasoned that my ability to work independently was being assessed, so the fewer questions I asked, the better.

With two exceptions, when something was absent from the requirements, I either treated it as a stretch goal that I would add if time permitted or just decided not to implement it. For example, I fully supported VoiceOver in one solution, but, in the others, I merely called out in the readme that I would better support VoiceOver in a production app. My coding-challenge solutions have had user-facing Strings sprinkled throughout and are therefore not internationalized, but, similarly, I have called out the importance of internationalization in my readmes. I’ve never made a custom iPad layout but have noted in my readmes that iPad would benefit from higher information density or perhaps UISplitViewController, which I don’t use for coding-challenge solutions. I have noted in my readmes which Xcode version I used so that I didn’t have to bug my points-of-contact about that trivial detail.

I have always treated two requirements as present in all coding challenges, even if unstated.

One is unit testing and the dependency injection that powers it. The reason I treat this requirement as always present, even if unstated, is my observation, confirmed by recent strong performances on coding challenges, that experienced developers, the kind that review solutions to coding challenges, set great store by unit testing.

The other requirement I treat as always present, even if unstated, is image caching. The performance of UITableView with images loaded from an endpoint is, in the absence of caching, terrible. Worse, the radio fires up repeatedly for the same images as the user scrolls, needlessly crushing the battery. An app that performs terribly and needlessly crushes the battery would, in my view, reflect poorly on my skill as a developer. This would frustrate the purpose of completing a coding challenge, which is to convince reviewers of my skill as a developer. So I cache.

One coding challenge I completed explicitly invited questions. This was the one potentially involving a UICollectionViewLayout subclass. I wasn’t sure that this API was appropriate, so I felt comfortable confirming that with my point of contact. I asked, and he confirmed.

Decisions, Decisions

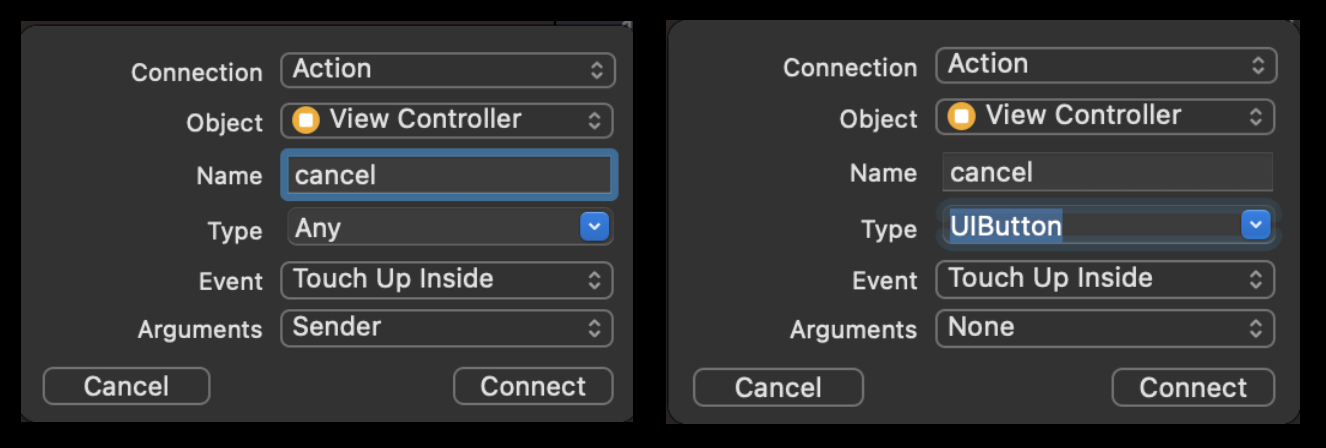

UIKit and SwiftUI are the dominant UI frameworks on Apple platforms, and you’ll likely have to decide which framework to use for your solution. An important factor in this decision is your relative skill levels with those frameworks. If you’re a UIKit expert with no knowledge of SwiftUI, a coding challenge is not the time to learn SwiftUI. The reverse is also true. Time may be limited, and you’re more likely to make newb mistakes when using a framework for the first time. A newcomer to SwiftUI might, for example, not make @State properties private. A newcomer to UIKit might neglect to change the default Type and Arguments of a new IBAction, a change shown here.

But relative skill level is not the only factor. If you are aware that the company either uses SwiftUI or plans to adopt it, but you are more skilled with UIKit, expending the extra effort to use SwiftUI in your solution might ultimately cause reviewers to rate your solution more highly. Or you could mostly use UIKit but mix in some SwiftUI via UIHostingController.

If you do use UIKit, you’ll need to choose between Interface Builder and programmatic layout. Either works, but the company may have a strong preference for the technique you didn’t use. If, for example, you use Interface Builder for your coding challenge, but you learn during an interview that the company strongly prefers programmatic layout, you should be able to say that you are comfortable with programmatic layout. This tutorial or inspection of the CatFancy codebase could help you build that comfort. Programmatic layout used to have an advantage over Interface Builder with respect to dependency injection, but that is no longer the case thanks to instantiateViewController(identifier:creator:).

With respect to the architecture to use in a coding challenge, there are competing interests. The Composable Architeture and VIPER have benefits with respect to unit testing, but I wouldn’t use those architectures for a coding challenge because they are likely unfamiliar to reviewers, unnecessarily complicating their reviews. Good ol’ MVC is likely familiar to reviewers, but that architecture makes unit testing more difficult because navigation code gets intermixed with view-controller code. I use a modified form of MVC, MVCC. The second C is the coordinator, an object responsible for navigation. Separating navigation and view-controller logic makes testing both easier, I have found.

Aside from coordinators, one modification of the classic MVC architecture involves use of view models. These are objects that take away from view controllers the responsibility for translating between models and user-facing UI. A view model might, for example, have a property userFacingFullNameInHungary: String that outputs Bartók Béla given a model with surname Bartók and givenName Béla. An MVC architecture with view models is called MVVM. View models are well-understood and widely used in the iOS-development community, and using view models in coding challenges may be appropriate. That said, my coding challenges haven’t had model-to-view translation logic that was complicated enough to justify MVVM.

Preparation

Preparation for coding challenges has two components, knowledge and practice.

With respect to knowledge, become familiar with dependency injection and how it facilitates unit testing. This is important preparation for not only coding challenges but also for job interviews, in my experience. There are many learning resources out there. I have found the following books helpful:

- “iOS Unit Testing by Example” by Jon Reid

- “Test-Driven iOS Development with Swift” by Dr. Dominik Hauser

- “Test-Driven Development in Swift” by Gio Lodi

You may find helpful two blog posts I’ve written, one about preparing an app for dependency injection, and the other comparing types of dependency injection.

Also become familiar with fetching JSON via URLSession, turning JSON into model objects via Codable, displaying images retrieved from an endpoint in a UITableView or List, and caching images. Those are all likely to come up in a coding challenge.

With respect to accessing REST endpoints via URLSession, I found “iOS Apps with REST APIs” by Christina Moulton helpful.

The practice component of preparing for a coding challenge involves actually completing a practice coding challenge. Here are many free endpoints you could use as a data source. You are also free to use the CatFancy endpoints.

You might consider using CatFancy as your own coding-challenge model solution. Don’t do that. I made a lot of decisions while developing that codebase. You have no access to my reasoning, but you might be asked for that reasoning during a job interview. For example, an interviewer might ask why you didn’t use constructor injection for your dependencies. Moreover, coding a model solution from scratch is a huge learning opportunity. Don’t miss out on that learning.

Completing a practice coding challenge has at least two benefits. One, assuming that your actual coding challenge has a strict time limit, for example two hours, having done a practice coding challenge might be the difference between success and failure. Two, assuming that your actual coding challenge has no time limit, having done a practice coding challenge could mean the difference between completing an actual coding challenge in thirty hours and six. If you have more than one coding challenge stacked up and/or work a full-time job, you might not have thirty hours to spend on a coding challenge.

As you contemplate your model solution, decide what add-on features you want to implement in actual solutions. Here are the add-ons that I implemented in CatFancy and that I have implemented in recent solutions:

- I implement a settings screen in addition to the required browsing screen. This screen provides a home for settings that control the app’s behavior, for example row sorting and alternate JSON to trigger error states. I also find that having two main screens better exercises the coordinator pattern.

- I implement row sorting, controlled via a setting, because many, though not all, coding challenges require a sort option. That said, sorting doesn’t make sense for some problem domains.

- I integrate SwiftLint for the tidiness benefit discussed in the section

Other Success Factors. If you haven’t used SwiftLint before, decide which default and non-default rules you prefer to enable. I have a preferred rule set that I use for every coding challenge. - I create alternate JSON files in addition to the main JSON file provided by the coding challenge’s endpoint. One JSON file has the same data as the provided JSON file but with more data added, often involving cats. I find that this extra data better exercises

UITableViewand image caching. Another JSON file has invalid JSON to trigger that error state. Another JSON file is devoid of row data and triggers the no-data error state. I store my alternate JSON files in AWS S3 buckets, which have publically accessible URLs, for example this one. - Relatedly, I implement error handling for invalid-or-empty JSON. This handling reports the appropriate error state to the user and includes a

Retrybutton that refetches the JSON. I implement this error handling for the reasons described in the sectionOther Success Factors.

When your solution is complete, annotate source files with comments about what needs to change for the domain of a specific challenge. For example, if your template app is about browsing cat breeds and has a file BrowseBreedsViewController.swift, which has sorting logic, put a comment in that file along these lines:

// TODO: Rename this file to reflect the domain.

// Change `Breed` and `breed` to `Foo` and `foo`, respectively, where the coding-challenge domain is browsing foos.

// Remove sorting logic if that doesn't make sense for the domain.

The benefit of these comments is that when the time comes to implement an actual solution, the implementation will go quicker. This comes in especially handy for challenges with a short, enforced time limit.

Ensure maximal unit-test coverage. If an object can be unit tested, create unit tests for it. If you can’t test an object because of its dependencies or side effects, use dependency injection to isolate those and enable unit testing.

Completing the Challenge

When the time comes to implement a solution to a real coding challenge, the steps you will take will depend, to some extent, both on the implementation of your model solution and on the requirements of the coding challenge. For illustrative purposes, I present here the steps I would take to turn the CatFancy codebase into a typical coding-challenge solution.

- Explore the endpoint. Pretty-printing the JSON makes understanding its format and contents easier.

- Determine what fields in the JSON correspond to UI elements required by the challenge.

- Create new JSON files with more data (

breeds_with_more.json), malformed JSON (breeds_malformed.json), and no data (breeds_empty.json). Store these files someplace you can access them viaURLSession, for example in an S3 bucket. - Copy all four JSON files into the app so that unit tests can quickly access them.

- Decide what navigation actions, if any, the user should be able to take from the details screen. These actions correspond to functions in the relevant coordinator conformances.

- Decide whether sorting is appropriate for the coding challenge and, if so, by what fields the user will be able to sort.

- Create a new UIKit-based iOS-app project. Delete

AppDelegate.swift,SceneDelegate.swift,ViewController.swift, andMain.storyboard. Recreate CatFancy’s groups in both the main and unit-test groups in the new project. CatFancy’s groups areAssets,Controllers,Delegates,Helpers,MockData,Models,Navigation, andViews. - Copy all source files from CatFancy to the new project.

- Comment out all domain-specific implementations and unit tests, for example those referencing the

Breedmodel orBreedDetailsVCsubclass. - Implement domain-specific sorting by modifying

SortOrder. - Make the relevant settings, specifically JSON URL and sort order, available throughout the app by modifying

Settings. - Uncomment the main navigation file,

MainTabBarVC.swift, and comment out references to specific coordinators andUIViewControllers. Modify this file so that the tabs are vanillaUIViewControllers. - Remove the storyboard reference from

Info.plist. At this point, the app should be runnable. - Implement the appropriate models for the coding challenge. For example, if the coding challenge is about browsing foos, whatever those are, create a

Codablefoo model inFoo.swift. - Implement JSON retrieval and parsing by modifying

BreedRequester. For now, useMainTabBarVCto test retrieval and parsing. - Implement browsing by modifying

BrowseBreedsVC,BrowseBreedsView,BreedCell,BreedCoordinate, andBrowseBreedsDeleSource. - Implement drilling down by modifying

BreedDetailVCandBreedDetailView. - Implement the settings UI by modifying

SettingsVCandSettingsView. - Uncomment domain-specific unit tests and modify them for the coding challenge’s domain.

- Replace CatFancy’s app icon with an appropriate Creative Commons-licensed image from Google Images.

- Write a readme.

- If delivery of the solution is via Zip file, zip the project, unzip it, and verify that both the app and unit tests work. If delivery is via GitHub, clone the repo and verify that both the app and unit tests work.

Contents of the Readme

Most challenges require a readme with certain content. Definitely include that content. I also include the following:

- Discussions of architectural choices and areas of emphasis. I discuss unit testing and the coordinator pattern. I find that most reviewers are interested in these subjects.

- What wasn’t included because of time constraints. I mention color palettes, iPad-specific layouts, VoiceOver, and internationalization.

- Discussions of any runtime warnings. A reviewer might assume that a particular warning results from programmer error, so if my research indicates that a warning is unavoidable, as it usually does, I note that.

- Required Xcode version. This is important because if the reviewer runs a different Xcode version than you used for your solution, the project may not build, or there may be new deprecation warnings.

- Screenshots. These give reviewers a head start on exercising the solution.

- Credits. These include both assets, for example the app icon, and concepts, for example testing app and scene delegates.

Parting Wish & Requests

I hope that you, the reader, derive benefit from this post as you prepare for and complete iOS-developer coding challenges.

I may use CatFancy in future as the basis for another solution of my own, so please let me know if you see any areas for improvement in the CatFancy codebase.

My experience with coding challenges may not be representative of what other candidates have experienced. I’ve created a Google Forms survey with questions like “In your experience, do the majority of coding challenges you have seen involve fetching JSON from an endpoint and displaying it in a UITableView or UICollectionView?”. Only four people have taken the survey so far, and I haven’t incorporated their answers into this post. But if you’re willing to take the survey, please email me. I will update this post with answers from survey takers when there are more of them.

Endnotes

-

This does not mean that I got offers from every company I applied to in recent years. I did not. But the non-offers had nothing to do with my solutions to take-home coding challenges. ↩

-

Paul Hudson, Peter Steinberger, and an anonymous member of the Applikey team have argued that

UITableViewshould be, will be, or has implicitly been deprecated in favor ofUICollectionView. Verily,UICollectionViewcan do everything thatUITableViewdoes and more. I would therefore not recommend avoidingUICollectionView. But I’m comfortable withUITableViewso, for the overwhelming majority of challenges I’ve completed that don’t requireUICollectionView, I’ve usedUITableView. ↩ -

The question of whether conformance to

UITableViewDelegateandUITableViewDataSourceshould be in one object or two is interesting. The single-responsibility principle might say no, to the extent that, on the one hand, “providing cells and the number of rows to aUITableView” and, on the other hand, “responding to events like a tap on aUITableViewrow” are distinct responsibilities. But I put conformance to both protocols in one object, which I call aDeleSource, because I see the two protocols as closely related, from a conceptual perspective. The runtime calls delegates conforming to both protocols as part of the lifecycle of the same object, aUITableView. This close relation is evidenced, I would argue, by the fact that conformance to both protocols often involves access to the same model, for example an array of cat breeds. ↩